PA Bill Number: HB469

Title: Amending the act of August 5, 1977 (P.L.181, No.47), entitled "An act providing for the acceptance by the Governor of jurisdiction relinquished by ...

Description: Amending the act of August 5, 1977 (P.L.181, No.47), entitled "An act providing for the acceptance by the Governor of jurisdiction relinq ...

Last Action: Re-committed to Appropriations

Last Action Date: Feb 3, 2026

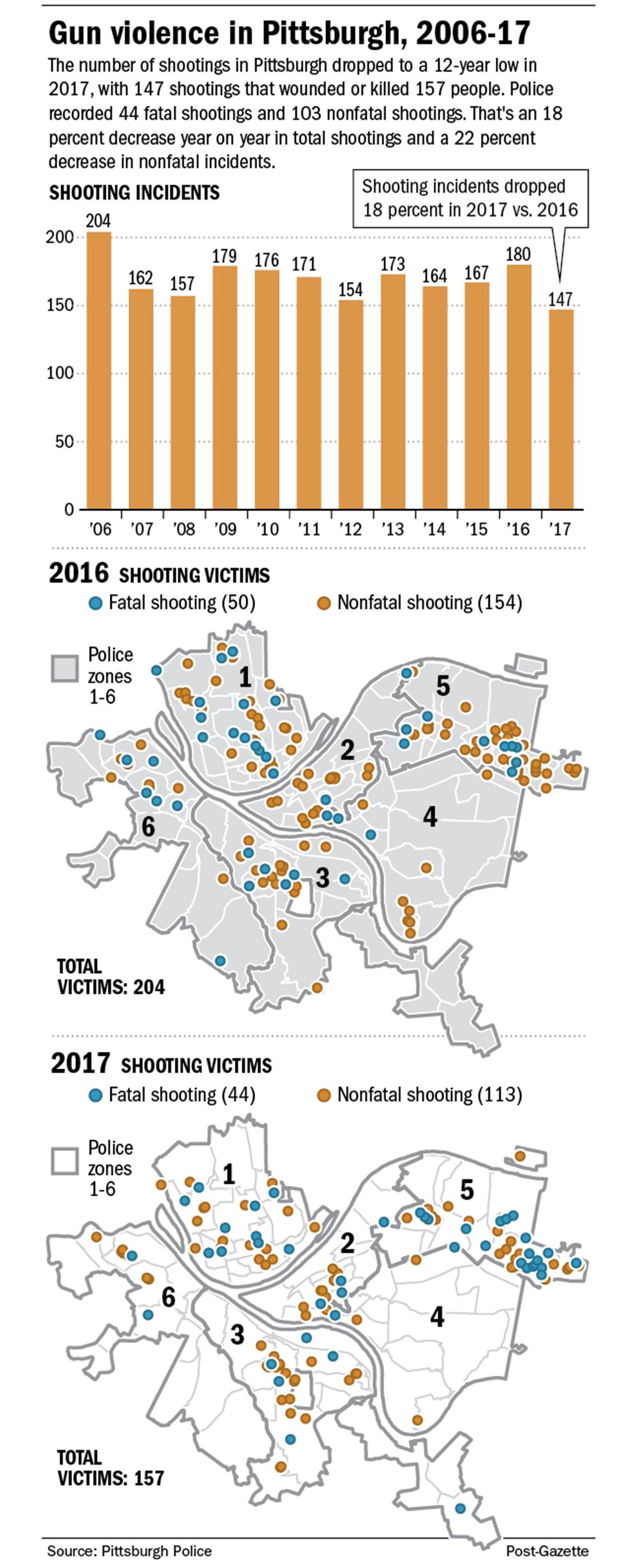

Pittsburgh gun violence drops to 12-year low; mayor credits police anti-gang efforts :: 03/22/2018

Gun violence in Pittsburgh dropped to a 12-year low in 2017, with police recording fewer than 150 shootings in the city for the first time in more than a decade.

Mayor Bill Peduto credited the decline to the daily efforts of officers on the streets, better community-police relations and to the city’s focused effort to quell gang-related gun violence.

There were 147 fatal and non-fatal shootings in the city during 2017, an 18 percent decline from 2016, which saw 180 shootings, according to police data obtained by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette through Pennsylvania’s Right to Know Act. That count excludes accidental and self-inflicted shootings.

“It’s a number we will constantly strive to lower, and there is no acceptable number as long as people are dying,” Mayor Peduto said.

Cmdr. Victor Joseph, who heads the police bureau’s violent crime unit, said his numbers show 188 non-fatal shootings in 2016 compared to 140 in 2017, a 26 percent decrease. Those numbers include self-inflicted and accidental shootings.

Through Tuesday afternoon, the city had seen 14 non-fatal shootings in 2018, Cmdr. Joseph said, compared to 31 through the same period last year — a 55 percent decrease.

He attributes the decline to the bureau’s Group Violence Intervention [GVI], a strategy that aims to reduce gang-related gun violence by targeting the city’s most violent gang members while also offering social services and support to those who agree to stop shooting.

The initiative zeroes in on those whom police believe are the most influential, and focuses both outreach and enforcement on those few individuals, Cmdr. Joseph said.

“It’s like a scalpel removing the problem rather than a machete,” he said.

Police revived the full effort in August after having bits and pieces of the initiative in place since 2015. Police use the term ‘group’ instead of ‘gang’ because they feel it better reflects the loose organization and shifting allegiances seen in the city.

In letters sent to city and county officials in February and March and obtained by the Post-Gazette, Assistant Chief Lavonnie Bickerstaff also credited the initiative for the 2017 decrease in non-fatal shootings and asked for continued support from officials as the city prepares to hold a ‘call-in,’ a formal meeting with the city’s most influential gang members.

During a ‘call-in’, which typically includes 20 to 40 gang members, officials explain how the strategy works, what members should expect and the consequences of continued gun violence.

They also tell gang members that help is available for people who agree to put their guns down, and emphasize if shootings continue, both the shooter and everyone in his gang will face the full force of law enforcement.

Chief Bickerstaff said in one letter that police created a list of people to bring to the first call-in. Since the list was compiled in late summer 2017, she wrote, five people on it were shot, four were killed and one was arrested for shooting three people.

Cmdr. Joseph said the police bureau is now planning the first call-in.

“It’s getting the message to the most influential members of the groups, letting them know what that message is and having it spread,” he said. “And hopefully they heed our warning.”

Of the 147 shootings in the city last year, 44 were fatal, according to the police data. That’s down from 2016, when 50 people were shot to death in the city. Shooting deaths in Pittsburgh have declined every year since 2014, when 59 people were killed, the data show.

“A lot of that credit goes directly to the officers,” Mr. Peduto said. “They have been able to make arrests of violent criminals that have been able to get them off of the street, and they also have been very engaged in the [violence] reduction program.”

He said police command staff have also made a concerted effort to keep community members and organizations informed.

Tim Stevens, chairman and CEO of the Black Political Empowerment Project, said he’s aware of a couple of specific incidents in which Group Violence Intervention efforts may have prevented violence, and thinks community-police relations have improved recently.

“If the community begins to see police more as an ally than an enemy, the community will be more willing and comfortable to share needed information on incidents,” he said. “And hopefully, in turn decrease the level of crime in the city.”

The revival of the Group Violence Intervention strategy — which failed the first time the city tried it in 2010 — is just one of a handful of new anti-violence tactics launched in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County during 2017.

The Allegheny County Health Department used grant money and contracted with local organizations to create trauma-response teams and street outreach teams that function both inside and outside Pittsburgh. The teams treat gun violence like a disease and focus on stopping its spread.

Volunteers on the trauma-response teams respond to homicides in a recreational vehicle, park at the crime scene and provide immediate mental health care and support to survivors, neighbors and community members. The street outreach workers try to prevent violence by fostering personal relationships with gang members and attempting to mediate disputes.

Richard Garland, an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh who is leading the outreach workers, said he’s found his staff is often able to prevent violence if they’re alerted to a brewing problem, but added that it’s hard to track.

“This is the issue when we talk about outreach and its effectiveness,” he said. “If we hear stuff, we can go holler at folks so it doesn’t get to the level where police have to deal with it. So, how do you report on being able to stop something if it never happens?”

Dr. Karen Hacker, director of the Allegheny County Health Department, said the teams are in the field daily.

“It’s an encouraging sign to see that the number of shootings within the city of Pittsburgh has decreased; however, gun violence is still a substantial problem in our county,” she said.

During the last 12 years, shootings in the city typically varied year by year by one to nine percent either up or down. Four times, the percentage change between years reached double digits, with a 20 percent year-over-year drop in 2007, a 14 percent increase in 2009, and a 12 percent increase in 2013.

The 18 percent decline in 2017 is the second biggest drop since at least 2006, according to police data.

Shelly Bradbury: 412-263-1999, sbradbury@post-gazette.com or on Twitter @ShellyBradbury. Staff writers Christopher Huffaker and Adam Smeltz contributed.